From Big State and Small Society, to Small State and Big Society: Reflections on Richard Cornuelle's Healing America

—Peter J. Boettke and Paola A. Suarez

[S]ociety performs for itself almost everything which is ascribed to government. . . .

So far is it from being true, as has been pretended, that the abolition of any formal government is the dissolution of society, that it acts by a contrary impulse, and brings the latter the closer together. All that part of its organisation which it had committed to its government, devolves again upon itself, and acts through its medium. When men, as well from natural instinct as from reciprocal benefits, have habituated themselves to social and civilised life, there is always enough of its principles in practice to carry them through any changes they may find necessary or convenient to make in their government. In short, man is so naturally a creature of society that it is almost impossible to put him out of it. . . .

The more perfect civilisation is, the less occasion has it for government, because the more does it regulate its own affairs, and govern itself; but so contrary is the practice of old governments to the reason of the case, that the expenses of them increase in the proportion they ought to diminish. It is but few general laws that civilised life requires, and those of such common usefulness, that whether they are enforced by the forms of government or not, the effect will be nearly the same. If we consider what the principles are that first condense men into society, and what are the motives that regulate their mutual intercourse afterwards, we shall find, by the time we arrive at what is called government, that nearly the whole of the business is performed by the natural operation of the parts upon each other.

—Thomas Paine, The Rights of Man (1984 [1792], 193-195)

Introduction

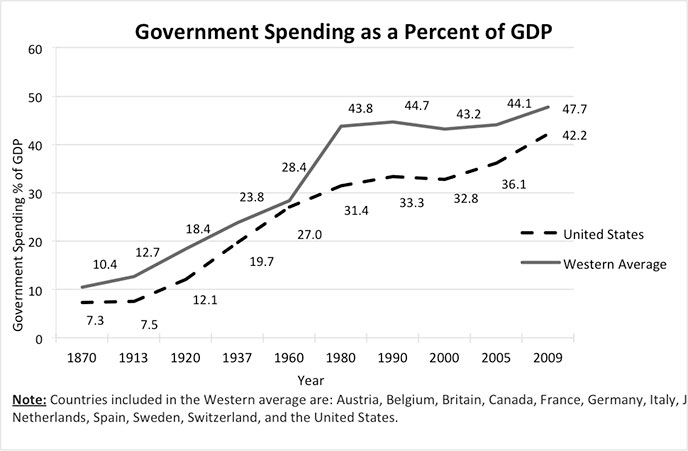

Government is a legitimized monopoly on the use of force in a given territorial region, whereas the state is the institutionalization of such a monopoly in society1. The twentieth century has witnessed a tremendous growth of government in the United States. In 1870, total federal, state, and local government spending as a percentage of GDP was 7.3 percent, in 1960 it was 27 percent, in 1980 it was 31.4 percent, and in 2009 it was 42.2 percent. As seen in Figure 1, among Western democracies, those numbers are slightly higher, with average government spending in 2009 being 47.7 percent of GDP, but the overall trend has been increasing government spending as a percent of GDP over time.

When Richard Cornuelle sat down in the early 1980s to write Healing America, there was a growing recognition that the Keynesian consensus in public policy was breaking down and that the public sector had become bloated and ineffective. But the policy steps that followed in subsequent decades did not take up the challenge as Cornuelle put it, and focused instead on ineffective efforts to constrain government spending. Cornuelle liked to borrow from Keynes the observation that you cannot become thinner by wearing a tighter belt. You have to trim the fat.

Figure 1: Government spending as a percent of GDP, 1870-2009.

Trimming the fat, Cornuelle argued, will result not from starving the state of resources but from starving the state of responsibility. To accomplish that we must demonstrate that the non-state sector is able to address the social problems which modern industrialization presents: mass unemployment, extreme poverty, provision of educational opportunity, and health and retirement services among others. A good society is one whose system of governance enables individuals to realize the gains from social cooperation and exchange under the division of labor, and thus experiences the benefits of material progress, individual freedom, and peace. A good society allows for free and responsible individuals who participate and have the opportunity to prosper in a market economy according to profit and loss signals, and who live in, and are actively engaged in, caring communities. As we will argue, a system of governance that allows such a society to emerge requires limits on the scope of government and reliance on the non-state sector to address many, if not all, of the actions we now assume only the state can accomplish.

Throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first the great expansion of trade and technology has produced a level of material wealth such that the costs of government intervention could be offset and remain largely hidden. This is not a new phenomenon—Adam Smith pointed out long ago how self-interest exercised through the market economy is so powerful in aiding the creation of wealth that it can overcome a “hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often incumbers its operations” (1981 [1776], 540). It is important to stress that the great material progress realized over the past 100 years was not caused by the expansion of state intervention into the economy but despite it, precisely as Adam Smith laid out. It is equally important, however, to stress that there is a tipping point where the costs of “impertinent obstructions” can simply no longer be offset nor hidden by the market economy.

The folly of human laws that intervene in the market economy is a consequence of ideas and interests. Government’s growth in terms of both scale (expenditures as a percentage of GDP) and scope (responsibilities) in the twentieth century has been astronomical. It has particularly accelerated in the twenty-first century as Western democratic states have had to deal with perceived tensions due to globalization and the widening income gap between the “West and the rest,” as well as the perceived terrorist threat from fundamentalist extremists who supposedly despise Western culture. But, as the fiscal situation in Europe and the United States has demonstrated so clearly over the past few years, the current scale and scope of government is unsustainable.

As already noted, government spending as a percentage of GDP has grown among Western democracies from an average of 12.7 percent on the eve of World War I to 47.7 percent in 2009 (Micklethwait 2011, Tanzi 2011). Spending has increased even more rapidly since 2009 in an effort to boost aggregate demand in the wake of the global financial crisis. Government spends because the economy is weak, and the economy continues to perform poorly because government spending crowds out productive private investment. It is a vicious cycle that has to be broken by a reevaluation of the role of government in a society of free and responsible individuals. This implies that the problem of the scale of government will only be addressed when we rethink the issue of scope of government. The important political/intellectual activity of our age is not to agitate to starve the state of resources, but to build the intellectual case that we can in fact starve the state of responsibility, as Cornuelle suggested in Healing America that we can and ought to.

Reevaluating the scope of government entails demonstrating that society can provide the necessary system of governance and acts of compassion to render state action needless. The belief in society’s ability to solve social problems without recourse to the apparatus of compulsion that is the state was a defining characteristic of democracy in America and the meaning behind a population of self-governing citizens. But modernity ushered in a new age—an age of great material progress along with the introduction of new social problems that challenged the quaint memory of caring communities. The belief in the self-governing capacity of individuals and communities to deal with social problems was lost, due intellectually to the transformation of public administration, which followed Progressive ideology, and empirically to the experience of mass unemployment during the Great Depression. Since then, not only have economics and politics been transformed to conform to the changed mindset, but American society itself reshaped into the image of a corporatist state ruled by trained experts who deal with social problems through the tools of state power rather than cooperation within communities.

Cornuelle argued that our intellectual culture since the Great Depression has “heard only the case for expanding the scope and size of government,” and that if “rationality is to be restored, the independent sector must compete for social responsibility consciously and aggressively” (1983, 174; 175). Success will require a radical rethinking of “public business” as the role of government in a free society is critically examined. In other words, it is necessary to engage in the negative task of demonstrating that the justificatory arguments for the state are not as airtight as imagined, and thus that the supply and demand for state action actually have their sources elsewhere. This demonstration is what we take as our task in this paper.

In sequence, we discuss the claims for state intervention that derive from our moral sense of justice, the arguments for state intervention based on prisoners’ dilemmas and the need for collective action, and the case for state intervention that follows from the broad claims of market failure. We then argue that even if we have good reasons to reject (or at least seriously question) the justificatory arguments for state intervention based on justice, collective action, or market failure, a high probability of state intervention will persist as suggested by public choice arguments regarding the logic of democratic governance. We thus turn to a discussion of what may be necessary to realize a society of free and responsible individuals who participate and can prosper in a market economy based on profit and loss, and who can live and be actively engaged in caring communities. We conclude by returning to Cornuelle’s Healing America and its implications for twenty-first-century political economy.

Moral Intuitions and the Moral Demands of the Extended Order

One of the greatest challenges to the unhampered market economy is the widely- held belief that wealth discrepancies are a result of ill-gotten gains, and thus destructive to social order. As a result of the disparity in income domestically and internationally, social tensions arise. Class war breeds real war, as the downtrodden rebel against the perceived injustice and use any means at their disposal to fight back. The idea of analytical egalitarianism (that we should strive for a politics that is characterized by neither discrimination nor dominion) becomes a political demand for resource egalitarianism, and the step from one to the other is taken without much thought.

The claim of injustice in the resulting distribution of income is deeply rooted in our evolutionary past, and thus intellectual challenges to our evolutionary inheritance have had difficulty sinking in regardless of their theoretical or empirical nature. As James Buchanan (1991 [1988]) put it, the great contribution of the classical political economists was the demonstration that autonomy, prosperity, and peace could be simultaneously achieved by the private-property market economy. It was precisely at the high point of their contribution’s empirical confirmation that the private-property market economy was criticized as an illegitimate form of social organization because of the injustice it permitted. The development of the marginal productivity theory of wages did not stop the spread of the moral belief that capitalism was unjust. The cold logic of economics clashed against the hot emotions of moral injustice.

Why does this tension exist? Economics is a scientific discipline that offers analytical explanations about how the world works, whereas moral theory offers normative suggestions about how the world ought to be. What if our moral intuitions about how the world ought to operate are at odds with the institutional framework required for the world to actually work such that individuals can live prosperous lives?

Hayek (1991 [1988]) postulated that this tension between our moral intuitions and the institutional demands of the extended order was a product of our evolutionary past. Human beings evolved in a setting where social cooperation required solidarity and altruism towards other group members over outsiders. Humans were thus conditioned by social norms appropriate for small-group living. The norms of face-to-face interaction adopted in such circumstances work for the intimate order of family and close kin. But with the emergence of specialization and exchange, our social interactions move far beyond intimates. As we enter the extended order of the nexus of exchange, the norms of the intimate order must give way to norms more appropriate for anonymous interactions that in fact restrain our evolutionary instincts regarding social cooperation. This does not mean that our moral intuitions regarding solidarity and altruism must be abandoned and replaced, simply that they must be constrained to the intimate order as they are insufficient for sustaining cooperation within the extended order. This tension is why, in Hayek’s view, “we must learn to live in two sorts of world at once” (18).

Adam Smith, too, recognized that our moral intuitions alone could not sustain cooperation among large anonymous crowds, while his treatment of intimate and face-to-face interaction among individuals was similar to Hayek’s. Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (1982 [1759]) uses moral sympathy, the ability to ‘enter into’ another’s situation by means of the imagination,2 as the foundation for the development of social rules and norms regarding acceptable/unacceptable behavior, justice, etc., and thus as conducive to social cooperation in such settings. Smith also considers benevolence and acts of kindness, as well as attempts to receive acts of kindness from others, as ways to induce cooperation. He remarks that man “has not time, however, to do this upon every occasion. In civilized society he stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes, while his whole life is scarce sufficient to gain the friendship of a few persons … man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only” (1981 [1776], 26). In Smith’s view, it is precisely because we obtain “the greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of” (26) through exchange in modern society that we rely not on benevolence or sympathy for social cooperation under the division of labor, but on self-interest.

When a father divides a candy bar between his two sons, it makes perhaps perfect sense to ask one to divide and the other to choose, and thus ensure a perfectly fair division of the fixed quantity of candy bar. Such rules of social division, however, make no sense when the dividers are unknown to the arbiter and the size of the “candy bar” is endogenous to how it is divided, as is the case of modern society. The puzzle that we confront is thus not how to ensure a fair division of a fixed amount of income, but instead to discover what set of rules will allow multitudes of strangers to live better together by exploiting mutual gains from specialization and exchange. Small-group cooperation must be replaced by large-group cooperation. As Hayek argued, the span of our moral sympathy can only stretch so far before our emotional instincts (such as solidarity, altruism, benevolence, and empathy) destroy our ability to realize the gains from social cooperation under the division of labor by preventing an extended order from arising altogether (1991 [1988]; see esp. 11-28). Small-group norms of social cooperation based on moral sentiments must thus be replaced by large-group institutions of governance.

The inherited moral intuitions of our small-group cultural past (which laud the warrior protector or the judicious king) come to be replaced by the rule of law and the bourgeois virtues of ownership, hard work, and commercial innovation. Deirdre McCloskey (2006) has argued that it was this shift from the morality of the ancients to the ascendancy of the bourgeois virtues that brought about the miracle of modern economic growth that has improved the lives of billions first in Europe, then in the United States and eventually throughout the world.

The state is not required to intervene to rid a presumed injustice regarding income discrepancies that arise in a truly free market economy because individuals earn profits by satisfying the demands of consumers. It is the lure of profit that not only alerts the businessman to opportunities for mutually beneficial exchange but also spurs the great gains from technological innovation. Competition drives costs down and product quality up. Businessmen earn higher profits only by better meeting and better satisfying consumer demands. Ultimately, it is the buying and abstaining from buying by consumers that determines whether a commercial venture is profitable or not. Individual riches within the unhampered market economy result only from productively utilizing resources to satisfy consumers better than one’s rivals. There simply is nothing unjust about such a distribution and thus no remedy is necessary. Yes, Bill Gates has greater wealth than we, but only because he better met the demands of a far greater multitude of individuals.

Curbing Private Predation, Creating Public Predation

In addition to the demand for the state to right economic injustice, curbing private predation is another argument often resorted to in an effort to increase the demand for state intervention. At the most basic level, this argument is used to justify the very existence of the state since, without a sovereign to define and enforce property rights, life, it is said, would devolve quickly into a war of all against all, becoming “nasty, brutish and short.” Everyone would be better off if they cooperated with one another, but the opportunistic among us would be even better off if everyone else cooperated while they engage in predation to confiscate the wealth created through others’ cooperation. Expecting others to predate, an individual’s best strategy is also to forgo cooperation and engage in predatory behavior. The only way out of the mutual-predation equilibrium, it is argued, is to establish a third party enforcer with the power to curb private predatory behavior by force: the state.

The problem with this approach to curbing private predatory behavior is that we create an entity capable of public predation to a far greater extent than any one private predator ever could imagine. Additionally, there has been much research in the past twenty-five years demonstrating that private predation can be curbed through rules of private self-governance that emerge independent of such a public entity, and many times despite it (see, for example, Leeson 2003, 2006, 2008; Caplan and Stringham 2008; Friedman 1979). Faced with collective action problems, communities can resolve conflicts through the evolution of rules that (a) limit access to common resources, (b) assign accountability, and (c) institute graduated penalties for violators. In small group settings, this is mainly done through reputation and ostracism. In larger group environments, however, where actor identity is not so easily discerned, social cooperation under the division of labor requires mechanisms that limit exposure to the downside risk of cheating and effectively discipline the guilty when cheating occurs. If private self-governance is to achieve such cooperation, both deterrence and effective punishment must be instituted without recourse to a governmental entity altogether, or at least, for the sake of the argument at hand regarding the size and scope of the state, without expansion of the role of government.

Curbing the predatory nature of mankind does not render inevitable the existence of the state or state expansion beyond a basic framework that provides for peaceful coexistence. Though mankind has historically exhibited a propensity for violence, we have also found ways to overcome or constrain that propensity and have thereby realized great gains from peaceful social cooperation through specialization and exchange. There are, then, at least two human propensities that history has repeatedly confirmed: (1) to truck, barter, and exchange, and (2) to rape, pillage, and plunder. Which propensity dominates is ultimately a function of incentives:3 the “rules of the game” human beings find themselves interacting within. If taking is possible only when coupled with giving, then the truck, barter, and exchange propensity will be on display. If taking is possible without any corresponding giving, then our propensity to predate on one another will be on display, which will tend to reward the strong and penalize the weak. But here is the trick: worlds that cater to our cooperative propensity grow rich and the lives within them are healthy and wealthy, whereas worlds that cater to our propensity for violence subject their inhabitants and, ultimately, even those who rise to the top of the predatory elite, to a life of ignorance, sickness, poverty, and squalor (see, for example, Leeson 2010; Boettke and Subrick 2003).

The state, as the institutionalization of the geographic monopoly on the legitimized means of coercion, is put in the advantaged position to predate and violate the human rights of its citizens and impoverish the population. Empowering the state to curb private predation requires the possibility of public predation. At each step of an argument demanding an increasing role of the state in the economy, this simple fact must be stressed, and multiple fail-safes established. David Hume (1907 [1754]), Adam Smith’s good friend and fellow Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, stressed that when designing governmental institutions we must assume that all men are knaves and require that the appropriate constraints are built in to ward off knavish behavior even if knaves are in power. A robust political economy, similar to what classical political economists wanted to establish, is one that builds in constraints on the predatory ability of government such that bad men will do the least harm if they get in power. Such constraints are inconsistent with an ever-expanding size and scope of government, as it entails disregarding the inevitably enhanced predatory capacity of the state.

Market Failure as Justification for Impediments to Market Adjustment

Economists’ justification for government intervention into the market economy stems from market failure theory. The four basic market failures are: (1) monopoly, (2) public goods, (3) externalities, and (4) macroeconomic instability. The concern for monopoly can be traced back to classical economists,4 though, by their definition, a monopoly was the possession of a state license to be an exclusive seller: monopoly power was a creation of state intervention, not of market forces. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, many economists started to argue that monopoly power was an outgrowth of competitive capitalism. Empirical evidence and theoretical developments concerning market theory have effectively challenged these arguments and demonstrated that the classical economists’ understanding of monopoly is the more coherent explanation of monopoly power.5 Nevertheless, in the popular imagination the idea that monopoly power is an outgrowth of unbridled capitalism dominates.

Classical economists argued that public goods resulted in a demand for increased state intervention into the economy. Roads and bridges, for example, would not be provided by the market economy because individuals could benefit from them without having to pay for that benefit and, given their self-interested nature, no one would pay. The “free rider” problem would impede the ability of firms to profitably provide these services. A free market economy, classical economists argued, would thus fail to satisfy consumer demand for such goods. This intuition was developed over the years into a pure theory of public goods. As with monopoly, however, more recent developments in theory accompanied by empirical investigations have demonstrated the existence of technological solutions to the “free rider” problem, and illustrated these with numerous examples throughout history where Coasean bargains have enabled private solutions to public good problems (see, for example, Ostrom 1990).

The economic theory of external effects developed more or less in the twentieth century.6 The argument is that left to its own devices, the market economy will often overproduce economic “bads” and underproduce economic “goods” because the private costs accounted for in decision making are not aligned with the social costs. The “invisible hand,” it is argued, fails to reconcile the differences in such instances. More careful examination, however, reveals that the primary reason for the breakdown in the reconciliation of social and private costs is the costliness of defining, assigning, and enforcing property rights. Pollution is a classic example: the market will overproduce pollution due to the incomplete definition and poor enforcement of property rights over the air. If we could clarify and enforce property rights, then all costs and benefits associated with the use of a resource in production would be internalized to the decision-maker, thus aligning social and private costs. In the case of pollution, assigning and enforcing property rights over the air would reduce pollution to its ‘optimal’ level.

Contemporary developments in economic theory and empirical investigations have demonstrated that the Pigouvian approach of state intervention to remedy externalities was either redundant or inoperable.7 Empirically, there are numerous examples where individuals engage in Coasean bargains to transfer property rights and internalize externalities, as well as technological advances that enable individuals to internalize what previously was an externality.8 Today’s inefficiency represents tomorrow’s profit opportunity for the entrepreneur who can address the inefficiency effectively. State intervention thwarts the entrepreneurial process of discovery and market adjustment by individuals, and proposes instead a political solution.

Finally, the most significant claim for state intervention into the market economy in modern times comes from the argument regarding macroeconomic instability. This argument maintains that the unhampered market economy is unstable and suffers from periodic crises which bring uncertainty about the future, as well as the social ill of unemployment and thus poverty. The Great Depression destroyed an entire generation’s faith in the unhampered market economy in Western democracies such as the United States and United Kingdom. (It took close to fifty years for a revival of market-oriented thinking. Though since 2008, the Great Recession has once again challenged the faith in the unhampered market economy.)

Just as in the case of the Great Depression, however, a closer examination of the Great Recession reveals government policy as the source of the economic distortions that led to the economic disruption. The length and severity of the crisis, as well as the slow recovery, have been due to the continued implementation of failed monetary and fiscal policies and to increased regulations and restrictions that inhibit market adjustment. It is, in fact, the very government policies adopted to curtail the necessary market adjustments that turned what would have been a market correction into an economy-wide crisis.

Public Choice Problems, Not Market Failure, are the Reason for Intervention

We have laid out the arguments from social philosophy (justice), political theory (collective action), and economics (market failure) for the necessity of government and government intervention in the market economy and have suggested in each instance that theoretical developments and empirical investigations have challenged each of these rationales for government and government intervention. For the sake of argument, assume the case for zero government intervention is persuasive. We contend that, even in the case where we all are persuaded that state intervention is unnecessary, the erosion of the constraints on democratic action and standard public choice theory predict that state interventions into the market economy will nonetheless take place.

Independent of any intellectual argument demanding state intervention, the political process is governed by the vote motive on the demand side and vote-seeking behavior on the supply side. Political exchange has a strong tendency to concentrate benefits on the well-organized, well-informed, and especially interested voters in the short run, and to disperse the costs on the unorganized, ill-informed, rationally ignorant voters and rational non-voters in the long-run. The bias toward shortsightedness in politics induces policymakers to favor policies that have immediate and easily identifiable consequences, while overlooking policies that have only long-term consequences, even if they are wealth-enhancing. The short-sightedness bias cuts against the standard argument, often promoted by advocates of state control over the economy, that profit-maximizing behavior will not appropriately calculate the returns to long-term investment. In fact, as multiple studies of the conservation of natural resources within a setting of well-defined and enforced property rights have demonstrated, the market economy does effectively allocate investment funds over time (see, for example, Anderson and Leal 1997).

Government, by definition, holds a geographic monopoly on the legitimized use of coercion, and as such there is a strong incentive for individuals to capture this powerful entity and benefit themselves at the expense of others. The problem is essentially as follows: government can be and will be used by some to benefit themselves at the expense of others unless its power is somehow effectively constrained to protection and not predation (Niskanen 1994 [1971]; Tullock 1965, 1992; Stigler 1971).

As the social philosophy, political theory, and economics arguments listed above become more persuasive, the demand for state intervention grows stronger, as these have been deployed to clarify the constraints on government action. Absent these arguments, however, the opportunity for strategic use of government power to benefit favored groups over others will put constant pressure on any constraints on government, if not render them meaningless.

Politics without Discrimination or Dominion

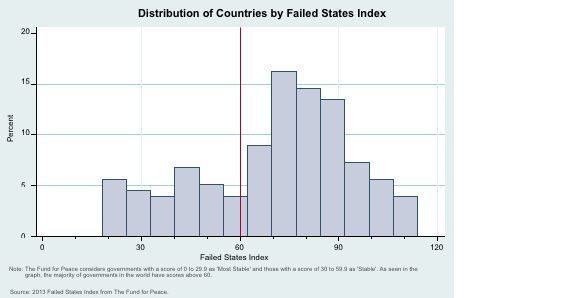

James Buchanan (1999 [1975]) divides the economic role of government into three distinct categories: (1) the protective state, (2) the productive state, and (3) the redistributive state. A wealth-creating society will empower the protective state (law and order) and the productive state (public goods such as infrastructure), and it will constrain the redistributive state. A distortionary state, on the other hand, will unleash the redistributive state, which rewards and induces rent-seeking behavior, and thwart the wealth-creating capacity of the protective and productive state, which rewards and induces productive behavior. The puzzle of modern political economy, according to Buchanan, is to find constitutional rules that enable a wealth-creating society. That is, rules which empower the state such that it may carry out its protective and productive tasks, but prevent it from engaging in redistributive tasks. Simultaneously empowering and constraining government, however, if not unattainable, has proven more elusive than originally thought. This difficulty is evidenced by the fact that less than 30 percent of the world’s governments are considered ‘stable’, as shown in Figure 2.9

Figure 2. Distribution of countries by failed states index:

Source: 2013 Failed States Index from The Fund for Peace.

Note: The Fund for Peace considers governments with a score of 0 to 29.9 as 'Most Stable' and those with a score of 30 to 59.9 as 'Stable'. As seen in the graph, the majority of governments in the world have scores above 60.

Consider the current financial crisis and the role of fiscal and monetary policy. Adam Smith argued long ago that ancient as well as modern governments had a strong proclivity to endlessly engage in the “juggling trick” of running deficits, accumulating public debt, and then debasing the currency to monetize the debt (1981 [1776], 908-947). Bankruptcy, Smith argued, was the least dishonorable and least harmful policy, but it would rarely be followed. In our current situation, the endless cycle of deficit, debt, and debasement continues to plague economies in Europe and the United States.

Faced with these “juggling tricks,” the only way to constrain the state is to effectively tie the decision-makers’ hands or take away the balls that can be juggled. That is, we either have to establish binding rules for monetary and fiscal policy, or the responsibility must be taken away from the state altogether. Obviously, it makes no sense to talk about fiscal policy outside the sphere of state action. Monetary policy can be, however, and has historically for certain periods and in certain countries, been developed outside the domain of state action. So some combination of binding constitutional constraints, fiscal decentralization, and denationalization of money may provide the policy regime required to simultaneously empower and constrain government effectively.

Absent such drastic steps at restraint, there will be a strong tendency for the scope and size of government to grow. Though an increasingly larger role of government in society is not inevitable, given the difficulties of effectively constraining its power to predate while allowing it to retain its power to protect, it is highly probable. The Western democratic economies of Europe and the United States, for example, have reached a turning point in their history. Constant state intervention into the free market economy has already curtailed the wealth-creating capacity of the economy and has resulted in self-perpetuating fiscal irresponsibility and monetary mischief.

The Message of Healing America

The Great Recession has from the beginning, in our view, resembled the 1970s much more than the 1930s. Despite the intellectual defeat of Keynesianism among academic economists (see, for example, Hazlitt 1959, 1960; Friedman 1968, 1969;, Buchanan 1958; Buchanan and Wagner 1977), the essence of public policy throughout the West did not fundamentally change from the 1980s onward. Instead, there was an oscillation between conservative Keynesianism and liberal Keynesianism, but the use of public policy to manage the macroeconomic system was never abandoned. It has been business as usual since the end of World War II.

In Healing America, published in 1983, Cornuelle explains how the transformation of public administration reinforced the policy proposals of Keynesianism: “Keynesian economics was not so much accepted as swallowed” (50). Keynes’ economic ideas “provided what the world was waiting for: an elaborate rationalization of the festering antagonism to capitalism” (50). By driving a wedge between the automatic balancing mechanism of savings and investment, Keynes was able to aver that inequality, the thing people most disliked about capitalism, was a critical cause of mass unemployment, the thing people most feared about capitalism. Resentment and fear were thus united in one doctrine, and the proposed solution—demand management by the state—promised to reduce both and therefore ease social tensions.

The Progressive ideal of an educated elite at the helm of a professionalized policy bureaucracy was fulfilled institutionally as a consequence of two world wars and justified intellectually by the new doctrine of Keynes. The amateur efforts by community members to provide relief to those struck by misfortune would be substituted by the work of professional experts. Although the quaint memories of what communities’ accomplishments, such as barn raisings, could be looked upon with pride, they were decidedly deemed a thing of a bygone era far less complicated than our modern industrialized world, which brought great material wealth but also the misery of inequality and insecurity. Modernity demanded modern public administration, not faith in the reliability of individual acts of mercy and community engagement.

From 1900 through the 1940s, public administration was transformed in the United States, and the Keynesian doctrine was most suitable for this new science of public policy. Fiscal and monetary policy became tools for combating economic inequality and insecurity. “Government spending,” Cornuelle points out, “became its own justification, thought to have value as an economic stimulant, aside from the merits of the programs it financed” (1983, 63). Government spending, in other words, was deemed a productive activity in itself. Deficit financing took on a new legitimacy, as Cornuelle points out in an argument that dovetails with the work of James Buchanan and Richard Wagner (1977) in, Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes: “What had been an embarrassed last resort to be used only in time of war or catastrophe became the accepted medicine against the system’s most dreaded disability” (Cornuelle 1983, 65).

By the end of World War II, it was conventional wisdom in the United States, held firmly by both liberals and conservatives, that government was the only solution to social ills, and that the independent sector and the market economy could not address the problems which the modern industrial age presented. As Cornuelle writes,

The belief that government spending was the ultimate weapon against unemployment gave government an overwhelming advantage in the continuing contention for social responsibility. Overnight, in good times and in bad, almost every proposal for expanding the role of government had a powerful, seemingly conclusive new justification. By freeing government from the discipline of cost consciousness, the balance between the public and the independent sectors was radically—perhaps permanently—tilted in favor of centralization. (66)

In addition to shifting the intellectual balance of power, this change of perspective regarding government spending, the role of government, and the free market’s capacity for resilience unleashed Adam Smith’s “juggling tricks” mentioned earlier. An endless cycle of deficit finance, accumulation of public debt, and debasement of the currency in an effort to monetize the debt became the norm. The period of the so-called Great Moderation was actually a period of “economics of illusion,” where social problems were not eased, let alone erased, but merely papered over—literally. This is the diagnosis, we would argue, that follows from applying the logic of Cornuelle’s argument to the current circumstances. The debt problem in Europe is not fundamentally different from the debt problem confronted by various state governments within the United States, let alone the national debt problem confronting policymakers in Washington, D.C. Such problems didn’t emerge overnight, and they didn’t get to their current state of crisis by a single decade of bad policy choices, but through decades of continuously bad policies, often concealed by the same Keynesian policies that gave rise to the circumstances in the first place. This situation is nothing but a consequence of self-reinforcing statist policies and a complete rejection of the capacity for self-governance in both the market economy and the independent sector.

When Peter Boettke, one of the authors of this article, was a graduate student, James Buchanan presented the class with the following puzzle: A fly that grew to nine times its normal size, could no longer fly. The structural composition of the fly would be compromised by the enhanced size. It was an engineering problem of dimensionality. Buchanan paused, and asked, “What does this argument suggest about fiscal dimensionality and the functioning of government?” This seemingly simple puzzle has a tremendous capacity to leave one in bewilderment.

It makes one think about questions of the scale of government and whether there is an optimal size of government beyond which the system stumbles and fails. In wartime economies, for example, the share of GDP attributed to government within Western democracies can rise to 60 percent or higher. But this figure is misleading, as it focuses on an economy that has been transformed by the pursuit of a single end—to win the war. The normal operation of an economy is characterized precisely by the absence of any single overarching end and the continuous presence of conflicting individual plans. A free-market economy is means-related, not end-oriented. A multiplicity of ends that are often in conflict with each other are pursued at any one time. What isn’t in conflict is the means employed by actors to pursue their various ends. In this sense, an economy has no teleology, though each individual within the system definitely has a purposive agenda with regard to their own pursuits.

Government substitutes the diversity of individual plans with targeted policies. The budget is utilized as an instrument to achieve specific policy goals, but the endless cycle of deficit, debt, and debasement results in public debt crises and inflation simultaneously. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, politicians used the term “misery index” to describe a situation of simultaneous double-digit inflation and double-digit unemployment. The conclusion from this experience was that “in the long run inflation-producing deficits are not a cure for unemployment but a cause of it” (Cornuelle 1983, 75). The age of economic illusion produced little more than economic distortions requiring correction by market forces: misdirected investments had to be realigned, and distorted employment patterns meant labor had to be reallocated. The “recalculation” of economic activity, however, can only take place within a market economy, and government activism merely slows this process, thereby causing further distortions.

Prices must be free to be meaningful and accurately tell the story of economic reality. Tastes, technology, and resource availability must be allowed to assert themselves on the prevailing prices and profit and loss signals in an economy if the social gains from cooperation under the division of labor are to be exploited. The state has failed to control the economy and it has failed miserably to manage social ills, as a sober reflection on the history of the “war on poverty,” “war on drugs,” and “war on terror” reveals through a cost-benefit analysis. Our prisons are full, our cities continue to exhibit signs of collapse, unemployment hovers at 8-10 percent (without including long-term unemployment), and the young are ill-served by our public schools (primary through higher education) while their prospects for gainful employment are questioned by the designation of zero-marginal-product workers.

Conclusion

Cornuelle’s analysis of the problems faced in the 1980s is directly applicable to the situation we face today. This situation cannot be fixed by efforts to constrain the state, since it can only be addressed by a radical rethinking of the role of government in society altogether. It is not primarily a question of scale, but of scope. If we rethink the scope of government, then by necessity we rethink its scale. We don’t get thinner by tightening our belt, but as we get thinner, we require a smaller belt.

The radical message of Cornuelle is, for this rethinking of the scope of government to take place, we must move away from the progressive ideal of an educated elite populating professional bureaucratic organizations responsible for public policy, and instead embrace the amateur yet often compassionate efforts of private citizens in their communities as decentralized mechanisms of coping. We must once again restore faith that the effort by countless anonymous actors can indeed handle the most difficult problems associated with economic insecurity. We have to remind ourselves that a “social reality exists separately from the state” and “how much work is done is done not because of the state but in spite of it, and hence how much of society’s future will be shaped outside of the state” (Cornuelle 1983, 142).

“The healing of America,” Cornuelle wrote, “will require a sustained, systematic expansion of the independent sector deep into the domain now considered the territory of government” (173). For our purposes, this is not an ideologically inspired agenda, but a very pragmatic agenda. We simply cannot continue down the fiscal path we are on. The big-state, small-society policies that dominated the twentieth century and have continued into the twenty-first with renewed vigor must give way to a small-state, big-society vision if our fiscal house is to be set in order and we are to bequeath our grandchildren a free and prosperous commonwealth. The nation’s current system of government does not have the appropriate institutional structure to provide effective countervailing constraints to government power. Neither the political structure nor the voting booth provides enough disciplinary feedback to keep government policy in check.

As Cornuelle has argued, the Progressive Era ushered in governments that chose one particular method for solving social problems. They sought to professionalize the public business, employing an educated elite at taxpayers’ expense, overlooking the high costs of this enterprise since, within the Keynesian system, public spending was inherently justified. What is required, then, is a de-professionalization of public business and a conscious and sustained effort to “involve the energies of people and their primary institutions rather than excluding them” (Cornuelle 1983, 179). In short, we need a rebirth of community.

“In the end,” Cornuelle concludes, “a good society is not so much the result of grand designs and bold decisions, but of millions upon millions of small caring acts, repeated day after day, until direct mutual action becomes second nature and to see a problem is to begin to wonder how best to act on it” (196). Cornuelle often stressed to those close to him how it frustrated him that, although we knew so much about how the self-regulating, free-market economy operates, we still knew so little about how a free society would work. There remains so much work for the invisible hands to do in a free society, and it resides outside both the commercial sector and the public sector.

NOTES

1 The classic definition of government, given by Max Weber in his essay “Politics as a Vocation,” is an entity which successfully “lays claim to the monopoly of legitimate physical violence within a particular territory” (2004 [1919], 33).

2 “As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation. Though our brother is upon the rack, as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform us of what he suffers. They never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations. Neither can that faculty help us to this any other way, than by representing to us what would be our own, if we were in his case. It is the impressions of our own senses only, not those of his, which our imaginations copy. By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them. His agonies, when they are thus brought home to ourselves, when we have thus adopted and made them our own, begin at last to affect us, and we then tremble and shudder at the thought of what he feels” (Smith 1982 [1759], 9).

3 See Becker (1968) for a theoretical account of individuals responding to incentives when choosing whether or not to engage in private predation.

4 See, for example, Mill (1866 [1848]) for an account of natural monopoly, and Smith (1981 [1776]) for a definition of monopoly that entails government creation. For a formal theory of monopoly see Cournot (1897 [1838]).

5 See, for example, Demsetz (1968), Coase (1972), Baumol (1982), Baumol et al. (1982).

6 The work of Arthur C. Pigou was instrumental in this area, in particular Pigou (1912, 1932).

7 The seminal paper here is Coase (1960). See Demsetz (1967) for how the process of assigning property rights and thus internalizing externalities depends on cost.

8 See, for example, Anderson and Leal (1991, 1997).

9 2013 Failed States Index, The Fund for Peace. Countries with scores between 0 and 59.9 are in the Stable or Most Stable categories; 51 out of 178 countries have scores in this range. Retrieved from: http://ffp.statesindex.org/rankings-2013-sortable. Accessed October 7, 2013.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Terry L. and Donald R. Leal. 1991. Free Market Environmentalism. San Francisco: Pacific Institute for Public Policy Research.

———. 1997. Enviro-Capitalists: Doing Good While Doing Well. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Baumol, William J. 1982. “Contestable markets: an uprising in the theory of industry structure.” American Economic Review, 72(1): 1-15.

Baumol, William J., John C. Panzar, and Robert D. Willig. 1982. Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Becker, Gary S. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy, 76(2): 169-217.

Boettke, Peter and J. Robert Subrick. 2003. "Rule of law, development, and human capabilities." Supreme Court Economic Review 10: 109-126.

Buchanan, James M. 1958. Public Principles of Public Debt. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

———. 1991 [1988]. “The Potential and Limits of Socially Organized Humankind.” In The Economics and Ethics of Constitutional Order, 239-251. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

———. 1999 [1975]. The Limits of Liberty. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, James M. and Richard E. Wagner. 1977. Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes. New York: Academic Press.

Caplan, Bryan and Edward P. Stringham. 2008. "Privatizing the adjudication of disputes." Theoretical Inquiries in Law 9(2): 503-528.

Coase, Ronald H. 1960. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3: 1-44.

———. 1972. “Durability and Monopoly.” Journal of Law and Economics 15(1): 143-149.

Cornuelle, Richard. 1983. Healing America. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

Cournot, Antoine A. 1897 [1838]. Recherches sur les principes mathématiques de la théorie des richesses. Translated by N. Bacon as Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth. London: Macmillan.Hea

Demsetz, Harold. 1967. “Toward a Theory of Property Rights.” American Economic Review 57(2): 347-359.

———. 1968. “Why Regulate Utilities?” Journal of Law and Economics 11(1): 55-65.

Friedman, David. 1979. “Private Creation and Enforcement of Law: A Historical Case.” Journal of Legal Studies 8(2): 399-415.

Friedman, Milton. 1968. “Why Economists Disagree.” Dollars and Deficits, 1-16. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

———. 1969. “The New Attack on Keynesian Economics.” Time (January 10).

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1991 [1988]. The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hazlitt, Henry. 1959. The Failure of the "New Economics": An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

———. 1960. The Critics of Keynesian Economics. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Hume, David. 1907 [1754]. Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, Vol. 1. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

Leeson, Peter. 2003. “Contracts without Government.” Journal of Private Enterprise 18(2): 35-54.

———. 2006. “Cooperation and Conflict: Evidence on Self-Enforcing Arrangements Among Socially Heterogeneous Groups.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 65(4): 891-907.

———. 2008. “Social Distance and Self-Enforcing Exchange.” Journal of Legal Studies 37(1): 161-188.

———. 2010. “Two Cheers for Capitalism?” Society 47(3): 227-233.

McCloskey, Deirdre. 2006. The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Micklethwait, John. 2011. “Taming Leviathan.” The Economist (March 19).

Mill, John Stuart. 1866 [1848]. Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy. Vol. 3, Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Niskanen, William A. 1994 [1971]. Bureaucracy and Public Economics. Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paine, Thomas. 1984 [1792]. The Rights of Man. Ed. Claire Grogan. Ontario: Broadview Press.

Pigou, Arthur C. 1912. Wealth and Welfare. London: Macmillan and Co.

———. 1932. The Economics of Welfare. London: McMillan & Co.

Smith, Adam. 1981 [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Vol. II of The Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith. Eds. R.H. Campbell, A. S. Skinner, and W. B. Todd. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 1982 [1759]. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Vol. I of The Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith. Eds. R.H. Campbell, A. S. Skinner, and W. B. Todd. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stigler, George J. 1971. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” Bell Journal of Economics and Management 2(1): 3-21.

Tanzi, Vito. 2011. Government versus Markets: The Changing Economic Role of the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The Fund for Peace. 2013. Failed States Index. http://ffp.statesindex.org/rankings-2013-sortable. (accessed October 7, 2013).

Tullock, Gordon. 1965. The Politics of Bureaucracy. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press.

———. 1992. Economic Hierarchies, Organization, and the Structure of Production. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Weber, Max. 2004 [1919]. “Politics as a Vocation” in The Vocation Lectures, 32-94. Eds. D. Owen and T. B. Strong. Trans. R. Livingstone. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.