Philanthropy, Economy, and Human Betterment: A Conversation with Kenneth Boulding

—Robert F. Garnett, Jr.

Introduction

The consensus among economists today, and indeed since Adam Smith, is that philanthropy plays no essential role in the formal theory or institutional structure of a complex, decentralized economy. As a bundle of noncommercial institutions and processes, philanthropy—“voluntary giving and association that serves to promote human flourishing” (Ealy 2005, 2)—falls outside the domain of standard economic theory (Mirowski 2001; Nelson 2006, 51). This theoretical omission is buttressed by the claim that philanthropic sectors are economically trivial in comparison with commercial and governmental sectors as generators and redistributors of wealth (Salamon 1995). 1

The economist Kenneth Boulding dissented from this consensus. Through a series of works written over two decades, Boulding crafted a suggestive reformulation of economic theory in which social cooperation and human betterment are promoted through a “grants economy” (which includes philanthropy) as well as an “exchange economy” (Boulding 1962, 1965, 1973, 1981). 2 At the same time, Boulding’s treatment of markets and philanthropy as separate spheres—the former propelled by self-interest, the latter by benevolence or moral sentiments—served to reinforce the economic denigration of philanthropy that Boulding ultimately wished to overcome.

My goal in this paper is to revise and strengthen Boulding’s treatment of the philanthropy/economy relationship by employing his own historiographic device, the “principle of the extended present” (Boulding 1971). The extended present, as Boulding defines it, is a space of conversation and mutual learning between canonical works and contemporary readers. Boulding developed this idea in his 1971 paper “After Samuelson, Who Needs Adam Smith?”, in which he argued that modern economists still need Adam Smith because his work contains untapped insights that challenge and complement present-day theories (Boettke 2000). I use the extended present here as a tool for putting Boulding’s work in dialogue with two innovative lines of contemporary thinking: the emerging literature of “new philanthropy studies” 3 and the wave of recent economic scholarship calling for an expanded view of economics and the economy, beyond the “separate spheres” treatment of self-interest and benevolence or the economy and civil society.4 By rereading Boulding in light of these contemporary literatures, and vice versa, I hope to contribute to the larger project of theorizing the central place of philanthropy in the “civil economies” of the twenty-first century.

The paper proceeds in four parts. The first section situates Boulding’s theory of philanthropy as a critical response to the Stiglerian, “Chicago” view of human nature, economics, and Adam Smith. The second section examines the theoretical shortcomings of Boulding’s formulation, particularly his treatment of markets and philanthropy as separate systems. The third section proposes a reformulation of Boulding’s scheme, inspired by an extended-present dialogue between Boulding and contemporary scholars of philanthropy and economics. The concluding section (“After Adam Smith, We Still Need Boulding”) reflects on Boulding’s enduring contribution to Adam Smith’s unfinished project: the recognition of philanthropy as a vital means of promoting human welfare through voluntary action.

Boulding ’s Revision of Philanthropy, Economics, and Adam Smith

When Boulding first surveyed the social science literature on philanthropy in the early 1960s, he was surprised to find little work by economists in this area, but he was confident that “the existing intellectual framework of economics [could] easily be expanded to incorporate the grants economy” (1981, vi). His 1962 essay “Notes on a Theory of Philanthropy” opens with a sober yet hopeful assessment:

In view of the importance of philanthropy in our society, it is surprising that so little attention has been given to it by economic or social theorists. In economic theory, especially, the subject is almost completely ignored. This is not, I think, because economists regard mankind as basically selfish or even because economic man is supposed to act only in his self-interest; it is rather because economics has essentially grown up around the phenomenon of exchange and its theoretical structure rests heavily on this process (1962, 235).

Eleven years later, after his professional peers had responded with “not always polite skepticism” to his argument that “grants economics should be a regular subdiscipline within the larger field [of economics],” Boulding’s assessment was more critical and combative:

One of the odd things about the grants economy is that it seems to arouse great anxiety and hostility among many more traditional economists. I admit I am a little puzzled by this, as a grants economy seems to me a very natural and obvious extension of the existing frame of thought in economics and in the social sciences generally. . . . The very hostility which the concept arouses, however, suggests that there is enough novelty in it at least to upset those whose economics is confined very strictly to the concepts of the exchange economy (1973, 10).

Boulding realized that in order to make room for philanthropy in economic theory, he would have to overcome the formidable “anxiety and hostility” of economists who believe that economics ought to be “confined very strictly to the concepts of the exchange economy."

This narrow view of economics is frequently ascribed to Adam Smith— specifically, the “Chicago Smith”5 who is purported by George Stigler and others to have argued that “humans can be represented as homo economicus, beings driven by a single motive: personal utility maximization,” and that market exchange is the only viable form of large-scale, voluntary social cooperation (Evensky 2005, 245-264). 6 In Boulding’s day and in our own, these “Chicago Smith” assumptions make it possible for economists to dismiss (or simply overlook) philanthropy as a topic ill-suited or unimportant for economic analysis.

Smith’s work, to be fair, contains numerous passages consistent with the Chicago point of view. In his Index to the third edition of the Wealth of Nations, for example, Smith declares self-love to be “the governing principle in the intercourse of human society” ([1776], 1976b, 1069). Notwithstanding the conceptual distance between Smithian self-love and Stiglerian self-interest,7 such statements suggest that Smith did indeed regard self-interest as the only secure basis for large-scale social cooperation. This view is supported by standard readings of Smith’s famous paean to self-interested exchange in the second chapter of Wealth of Nations:

In civilized society, [the human individual] stands at all times in need of the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes . . . and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favor, and show them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. . . . [I]t is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages. Nobody but the beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens ([1776], 1976b, 26-27).

Smith’s butcher-brewer-baker example pits the efficacy and humanity of trade against the indignity and inefficacy of begging: rationally negotiated quid pro quo transactions among legal equals versus servile appeals to benevolence. This juxtaposition suggests strong practical and ethical reasons to prefer market exchange over philanthropy as a means of material provisioning, and it may help explain why Smith himself “does not give private benevolence associations much of a role in solving social problems” (Fleischacker 2004, 275).

In light of the enduring influence of these “Smithian” assumptions and arguments, one can hardly be surprised by economists’ tendency to treat philanthropy as external to economics proper, or to assign it no important role in the institutional structure of modern economic life. These, however, are precisely the elements of professional common sense to which Boulding took exception in making his case for an economic theory of philanthropy, as in the following four principles he outlined.

1. Human nature is poorly represented by the textbook image of homo economicus.

Boulding rejects the standard economic description of the human actor as a socially detached profit maximizer. 8 He grants that human action is purposeful, even rational in the sense that “people do what they think is best at the time,” but he accepts it only with the proviso that “what is ‘best’ . . . may include benevolence and moral sentiments as well as the most outrageously selfish of motivations” (Boulding 1976, 6-7).

Boulding defines benevolent actions as those motivated by a sense of identification with others (1981, 4; 1962, 239-240). Adopting one of the central themes from Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments ([1759], 1976a), Boulding argues that benevolent actions are made possible by our human “capacity for empathy, for putting oneself in another’s place [and] feeling the joys and the sorrows of another as one’s own” (1962, 239). Acts of benevolence, for Boulding, belong to a larger category of “heroic” actions—noncalculative decisions “in which the decision maker elects to do something not because of the effects the decision will have in the future but because of what he ‘is’ here and now, how he perceives his own identity” (1970, 132). Boulding cites “saints and martyrs of all faiths, religious and secular,” as extreme examples of heroic action. Yet he mostly emphasizes the “quiet heroism” of everyday life, “in jobs, in marriage, in child rearing, and in the humdrum tasks of daily life, without which a good deal of the economy might well fall apart” (134).

Contrary to the reductionist anthropology of the Chicago Smith, Boulding claims that benevolence, heroism, and other forms of self-sacrificing or grouporiented action are not aberrant or exceptional but instead are “an essential part of man’s nature—his need to identify with others, his need to expand his interests and concerns beyond the confines of his own body” (1965, 250).

2 . Philanthropy is a gift, not an exchange.

Boulding distinguishes philanthropy from exchange in two fundamental ways. In terms of basic accounting, he observes, exchange is “a two-way transfer of economic goods,” whereas gifts and grants are one-way transfers that entail “a change in ownership of economic goods from a donor to a recipient” (1973, 1). In addition, Boulding gives philanthropy a behavioral definition as “pure gift”: “an expression of [a person’s] sense of community with others” (1962, 240), “even if the community is as vague as the common humanity that unites the donor and the recipients” (1981, 4). 9

Boulding recognizes that philanthropic actions can (and often do) arise from “impure” motives such as fear or vanity. He theorizes a spectrum of grants, ranging from pure gifts inspired by love or benevolence to tributes compelled by fear or threat (1981, vi, 4). His general conclusion is that “in almost all grants we find a certain mixture of [these] two motivations,” love and fear. “These mixtures of love and fear are distressingly untidy,” he notes, “but they seem to characterize a great deal of human behavior” (1973, 5). Still, to emphasize the moral potential of such acts, Boulding defines philanthropy in terms of its benevolent ideal. “There is a real moral difference,” he argues, “between the gift which is given out of vanity and the desire for selfaggrandizement or the desire to be merely fashionable, and the gift which is given out of a genuine sense of community with the object of the donation. It is this sense of community which is the essence of what I regard as genuine philanthropy. . . . When we make a true gift, it is because we identify ourselves with the recipient” (1962, 239).

3 . Every modern economy includes a grants economy as well as a commercial economy.

The overall economy, as Boulding defines it, is an amalgam of markets and grants. “There are two parts to our economy: the exchange economy, in which you get a quid pro quo; and the grants economy, in which all you get is quid— you do not pay any quo” (Boulding 1968, 49; 1962, 235-236). Together, these two subsystems comprise the overall process of social provisioning, “providing the good things of life,” namely “those things which need to be provided if human life is to be secure, comfortable, happy, adventurous, dangerous, heroic, and whatever else we may want it to be” (1970, 139-140). Boulding’s “economy” is therefore defined as a space of provisioning (human betterment) 10 that includes both tradable and nontradable “good things”: ordinary commodities as well as civic goods such as “security from threat and violence, status and dignity, civil rights, social justice, equal status with others as a person, and other things which we think of as part of the political and sociological aspects of life rather than economic” (140). He refers to this enlarged economy as the “total social process” of provisioning, within which “the exchange economy and the grants economy [are] equal partners” (1973, 13).

It is worth noting that Boulding was not entirely comfortable with this allencompassing “provisioning” definition of the economy, since it includes what he terms “non-economic goods” (“such things as respect, status, affection, [and] prestige, . . . on which it is hard to put a price” [1973, 1]). In Boulding’s view, such goods are economic in the broadest sense because they contribute to human betterment, yet as unpriced non-commodities they lie beyond the scope of economic science (1970, 139-140). As a partial resolution to these conflicting definitions of economy, Boulding proposes a nested definition: a broad “economic problem” definition, including the provision of all goods (priced and unpriced), and a narrower “economic science” definition, including only the provision of “economic goods” (money and commodities). 11

This ambivalence in Boulding’s definition of economy is significant, especially in connection with his theory of philanthropy, because it points to unresolved tensions between two parts of his intellectual identity: the economist and the humanist, the scientist of exchange and the scientist of humankind. We consider this tension later in this paper.

4 . Adam Smith's legacy in economics is a rich vision of human action and social cooperation that derives jointly from "The Wealth of Nations" and "The Theory of Moral Sentiments."

Boulding’s reading of Smith (1970, 117-138) underpins his arguments for principles 1, 2, and 3. Boulding’s general view of human nature and his conceptualization of philanthropy as benevolence are drawn directly from Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. In addition, Boulding’s “separate spheres” conception of the exchange and grants economies seems to reflect a common 1960s view of the relationship between Smith’s moral and economic theories.

Boulding’s appeal to Smith serves two important purposes. First, it brings Adam Smith’s writings into the extended present of modern economics as a living text still capable of teaching important lessons (Boulding 1971). Second, it gives a less radical complexion to Boulding’s critique of economic theory. Instead of arguing that existing economic theory “has it all wrong,” Boulding stresses the nascent intellectual potential of its Smithian heritage and speaks of philanthropy as simply a road not yet taken by professional economists: 12

On the whole, economists . . . have concentrated heavily on the concept of exchange in describing social relationships and the organization of society, and they have regarded the one-way transfer, or “grant,” as exceptional and apart from the general framework of economic or social theory (1973, 1).

The way forward, Boulding suggests, is not to reject standard economic theory but to expand it, on the premise that the development of a satisfactory theory of philanthropy will require nothing more than the “natural evolution of the existing conceptual framework in economics and in the other social sciences” (1973, 10).

In all, by challenging key premises of “Chicago Smith” economics, Boulding was able to build a cogent case for why economists should recognize philanthropy as a core element of human nature, the modern economy, and modern economic analysis.

Boulding’s work thus brings philanthropic gifts and associations into the economic domain and opens the door to a rich and robust economics of philanthropy. Moreover, his theory places a distinctive emphasis on the fluid, heterogeneous, “messy” character of social phenomena. Alongside his categorical distinction between markets and grants, Boulding’s theory stresses that real-world grants and exchanges form a continuum, with “ordinary acts of exchange at one end and charitable gifts on the other, but with a great many intermediate forms and stages” (1962, 237). He takes a similarly spectral view of the distinction between gifts and tributes and of the sub-distinction between gifts to known and unknown others. Altogether, Boulding envisions an untidily pluralistic economy that enhances human betterment through the commercial and philanthropic provision of civic and market-traded goods. This complex economy coincides with Boulding’s view of human action as perpetually driven and constrained by a messy mixture of selfish and moral sentiments.

Boulding's Incomplete Break from the Chicago Smith

Despite the fluidity and openness of Boulding’s framework, he ultimately achieves only a partial break from the economics of the Chicago Smith. Because he honors the disciplinary tradition of treating market exchange as a self-contained system, Boulding can introduce philanthropy only as a separate and parallel system vis-à-vis the market system. This reinforces the very market/philanthropy dualism that has long underwritten the exclusion of philanthropy from economic science. Even while stressing that benevolence and philanthropy are just as “integral” to human nature and human betterment as self-seeking and market exchange, Boulding still treats markets and philanthropy as two separate spheres, each with its own “laws of motion”—the market economy driven by self-interest, and the grants economy driven by benevolence. Regarding the latter, Boulding argues, “Despite the significant role that threat, or the fear of consequences, plays in the development of a grants system, I am prepared to argue that the ‘integrative’ or gift element in grants ultimately dominates and determines both the overall extent of the grants economy and also its patterns and structure” (1973, 5).

This is a rare moment of essentialism in Boulding’s thinking. It may reveal a compromise he felt compelled to strike with an intellectually conservative profession in the hope of gaining greater respect and acceptance for his ideas (Boulding 1981, vii). It may also reflect the Cold War period in which Boulding’s theory of philanthropy was initially conceived, particularly the interlocking dichotomies of self-interest/benevolence, capitalism/communism, and - markets/philanthropy that was taken for granted by many U.S. economists circa 1960. In any event, by reifying rather than rethinking the market/philanthropy dualism, Boulding fell short in his attempt to recast the “intellectual framework of economics” so that markets and grants could become “equal partners in the total social enterprise” (1973, 13).

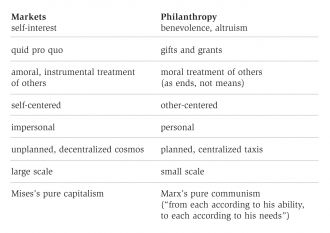

One practical consequence of this dualism is to place uncomfortably narrow limits on theories and practices of economy and philanthropy. It confines economy and economics to a Hobbesian world of narrowly self-interested exchange: heartless and amoral, yet uniquely effective in promoting human betterment on a large scale. Philanthropy is cast in a similarly narrow image: morally satisfying and practically effective on small scales but incapable of providing significant, systemic flows of economic goods and services, because of the absence of market competition and feedback. Schematically, the dualism is characterized by the elements in the following table:

These conceptual oppositions limit Boulding’s ability to theorize the economic dimensions of philanthropy and the humanitarian aspects of economics and the economy. For example, consider how Boulding’s market/philanthropy schism limits the scope of the “general theory of benefaction” he outlines in “The Difficult Art of Doing Good” (1965). Boulding begins this essay by positing a broad definition of “doing good” (contributing to human betterment) and argues that social scientists need to develop a consequentialist theory of benefaction, focused not on actors’ plans and intentions but on how and how well private actions actually advance human betterment (1965, 247-251). He further proposes that the study of benefaction should be interdisciplinary, as an antidote to the narrowness of standard economic theory and economists’ general failure to provide practical solutions to complex social problems such as “development” and “urban poverty” (1970, 152-154).

Yet within the segregated structure of Boulding’s framework, the term benefaction is limited to the category of philanthropic gift. Boulding is unable to extend it to include unintentionally benevolent effects of market exchange. [13] Boulding takes one suggestive step in this direction by broadening his definition of “philanthropic gift” to include gifts to unknown others, as when he writes, “We relieve the necessities of the poor for very much the same reason we do not allow our own children to starve—because they are, in some sense, part of us” (1965, 253). This suggests a philanthropic analogue to Smith’s extended moral order whereby the reach of philanthropy would be limited only by the extent of our moral imaginations. Yet such an extended, Smithian notion of benefaction—as including both intended and unintended advances in human betterment through voluntary action and interaction—is strictly inconceivable within Boulding’s conceptual scheme.

Extending Boulding's Legacy: Beyond the Market/Philanthropy Dualism

In recent years, leading economists across the ideological spectrum have argued for a broader vision of economic life—beyond the received dualisms of self-interest/benevolence and economy/civil society. This diverse movement includes experimental economists (V. Smith 1998), development economists (Sen 1999), feminist economists (Folbre 2001, Nelson 2006), post-Marxist economists (Elster 1990, Gintis et al. 2005), and libertarian economists (McCloskey 2006a and 2006b, Storr forthcoming). Though few acknowledge intellectual debts to Boulding, their shared aim is to make room in economic analysis for richer understandings of human behavior and modes of provisioning, especially the provision of public (civic) goods outside the traditional domains of the commercial economy, the family, and the state.

Part of the impetus and leadership for this reinvigorated “economics as moral philosophy” campaign comes from a new generation of Smith scholars (Sen 1987, Young 1997, Harpham 2000, Rothschild 2001, Jensen 2001, Otteson 2002, Fleischacker 2004, Evensky 2005) who emphasize the overarching connections between Smith’s moral and economic theories. In contrast to the Chicago Smith of Stigler et al., this revisionist literature describes a “Kirkaldy Smith” [14] whose economic philosophy is marked by a complex, multidimensional view of human nature, a normative commitment to social welfare based on a “rich, Aristotelian description of a flourishing life” (McCloskey 2006b), and an appreciation of markets and commerce as necessary but not sufficient conditions for the achievement of “equality, liberty, and justice” for all (A. Smith [1776], 1976b , 664).

Unfortunately, these new-wave scholars have so far paid very little attention to philanthropy. To a remarkable extent, they have perpetuated the Smithian tendency to “not give private benevolence associations much of a role in solving social problems” 15Jerry Evensky, for example, argues that Smith’s vision of the great society “requires the institution of laws and the development and inculcation of civic ethics that are consistent with the freedoms of a liberal society” (2005, 277). Yet his analysis makes no reference to philanthropic associations or gifts. Likewise, Jeffrey Young (1997) and Nancy Folbre (2001) speak of markets, states, families, and communities but not of philanthropic organizations and processes. 16

Julie Nelson is a notable exception. While she offers no theory of philanthropy, she criticizes standard economic theories for their complete neglect of nongovernmental nonprofit organizations and all forms of “economic activity that involves a one-way transfer of money, goods, services, and assets for which nothing specific is expected in return (2006, 50-51). As groundwork for her alternative vision, Nelson asserts a Boulding-like definition of economics as the study of the “provisioning of goods and services to meet . . . material needs” within and among communities (xi) and urges all citizens (including her fellow economists) to “recognize that the health of living, vital economies depends on our ethical decision making and our willingness to support relations of care and respect” (127).

All of these scholars could profit from the inclusion of Boulding’s theory of philanthropy within their “extended present.” Boulding’s arguments would challenge them to think anew about the potential role of philanthropy in their various (re)formulations of economics as a social and moral science. Conversely, this new economic thinking could cast valuable new light on Boulding’s oeuvre as well—suggesting new ways to appreciate, criticize, and reformulate Boulding’s ideas, particularly his theory of the grants economy.

Another body of work that could profitably join this conversation is the new philanthropy studies literature in which scholars are rethinking the ends and means of philanthropy through the lenses of classical liberalism, Tocquevillian democracy, and modern Austrian economics (Ealy 2004, 2005). Richard Cornuelle’s work is particularly important in this regard, both because of his pioneering contributions to the rethinking of the role of philanthropy in a free society and because of the striking parallels between his and Boulding’s separate efforts to introduce philanthropy into economic theory and vice versa (Cornuelle [1965] 1993, 1983, 1991).

Like Boulding, Cornuelle postulates a complex view of human nature, including a “service motive” which he defines as a “desire to serve others” ([1965] 1993, 55-64). On this basis, Cornuelle theorizes the structure and dynamics of a social subsystem (analogous to Boulding’s grants economy) which he terms the “independent sector”: a pluralistic array of voluntary, noncommercial social institutions that “takes a thousand forms and works in a million ways” and “functions at any moment when a person or group acts directly to serve others” (38). Cornuelle’s Tocquevillian goal is to build a society that is “both free and humane” (xxxiv) through the promotion of free markets as well as communal forms of voluntary public action outside of the marketplace and the state (Cornuelle 1991). 17In this respect, he and Boulding were initially motivated by similar desires to “find an alternative path to the good society other than those of the doctrinaire conservatives or the dogmatic liberals of the Cold War era” (Ealy 2002, 2; see also Cornuelle [1965] 1993, 3-19, and Boulding 1981, 112).

The work of Cornuelle et al. complements Boulding’s theory of philanthropy by providing a more sophisticated economics of philanthropy. In the tradition of Hayek, these scholars are highly attuned to the knowledge problems inherent in all deliberate efforts to promote human betterment. Their work also explores novel forms of philanthropic giving and association such as hybrid forms of commercial/philanthropic enterprise that move well beyond Boulding’s rudimentary image of philanthropy as noncommercial transfers from donors to recipients.

In addition, this literature poses a constructive challenge to Boulding’s political philosophy. Though Boulding is no unreflective statist, he tends to presume that the state can and should engage directly in the promotion of human welfare. 18 While Cornuelle would readily accept Boulding’s claim that economic libertarians generally have failed “to understand or to come to terms with” the philanthropic sector, and that the philanthropic sector “is an element of human life and human motivation that cannot be denied and cannot be neglected,” Cornuelle would strongly disagree with Boulding’s vision of the grants economy as including the welfare state, and he would oppose Boulding’s notion that “there should be no hostility between the libertarians and the welfare state” inasmuch as the welfare state represents an extension and embodiment of the philanthropic desire to help others (Boulding 1968, 47-48).

This portion of the conversation promises to deliver value in the reverse direction as well. The new philanthropy studies scholars could benefit from reflection on the normative foundations of their own efforts to foster “voluntary giving and association . . . to promote human flourishing” (Ealy 2005, 2). Boulding’s human betterment framework offers a fruitful starting point for such reflection. New philanthropy studies scholars might also benefit from the opportunity to rearticulate, in a Boulding context, their libertarian skepticism regarding state-sponsored efforts to “promote human flourishing.”

In sum, an extended-present dialogue between Boulding’s theory of philanthropy and these two rich streams of contemporary economic thought makes it possible to recognize Boulding’s continued relevance as an economic thinker. It also highlights pivotal tensions in Boulding’s thinking and suggests new strategies for resolving them.

Most importantly, this three-way conversation makes us aware of the tension in Boulding’s thinking between his allegiance to economics as a science of market exchange and his commitment to the larger enterprise of human betterment. It also makes us aware that current scholarship in philanthropy and economics is moving rapidly toward resolving this “Boulding dilemma” through various new syntheses of self-interest and altruism, markets and civil society, and so on. It is now possible, therefore, to reframe and reassert—with the backing of like-minded contemporary formulations—Boulding’s nascent argument that market exchange is an important subset of the social provisioning process while the main focus of economics as a science of human betterment is the “total social process” of “providing the good things of life” (Boulding 1970, 140). This conceptual reversal (making market exchange a special case of benefaction rather than the reverse) arguably follows the example of Adam Smith himself, who saw his Wealth of Nations as a subset of the general theory of moral and social order set forth in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (Otteson 2002). In any event, it suggests a promising way to bring the humanitarian and scientific aims of Boulding’s economics—and of modern economics generally—into alignment.

The implications of this reformulated Bouldingian economics would be threefold:

- a broader vision of economics, redefined as a science of benefaction dealing with how individuals “do good” for others through voluntary action and interaction;

- a broader vision of the economy, redefined as a “benefactory,” not just a commodity space or system of markets but instead a provisioning space in which economic cooperation and human betterment are effected via a plurality of commercial and noncommercial means; and

- a radically different view of the relationship between markets and philanthropy, seen not as a mutually exclusive dualism but as complementary and overlapping methods of addressing the basic economic problem, namely: how to achieve human betterment through voluntary social cooperation.

This expansive notion of a “civil economy” (commerce + philanthropy) redefines the philanthropy/economy relationship in ways that are arguably important for the twenty-first century. 19The range, magnitude, and dynamism of philanthropy today make it an essential part of any systematic economic analysis of how human flourishing is (or ought to be) promoted. Within the United States alone, annual giving now exceeds the total annual revenue of Wal-Mart and the GDP of many nations (Fulton and Blau 2005, 6). Furthermore, philanthropic initiatives are becoming increasingly important for the resolution of global crises, as exemplified by the impressive relief networks that emerged to support victims of Hurricane Katrina and the rapid coordination of international medical research to isolate the SARS virus in 2003. In an era of burgeoning government deficits and widening inequalities within and among nations, the philanthropic sector seems destined to bear a growing share of social responsibility for the welfare of the most disadvantaged global citizens.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to specify the conceptual and analytical details of this new approach, one essential theme must be noted. As a Boulding-inspired endeavor, this “benefactory” approach to economics would take seriously Boulding’s spectral view of social phenomena. No part of the economy would be conceived as inherently or exclusively “commercial” or “philanthropic.” The general presumption would be that every aspect of the economy is shaped and propelled by a mixture of commercial and philanthropic elements. Traits or features that economists might previously have ascribed exclusively to either markets or philanthropy would now be seen as general features of both markets and philanthropy—such as calculation (Boettke and Prychitko 2004; Chamlee- Wright 2004), reciprocity (mutual giving and learning), self-interest, benevolence, small-scale personal relations, large-scale impersonal relations, intended and unintended consequences, knowledge problems and social learning, integrative as well as disintegrative effects on individual identities and communities, elements of cosmos and taxis, and so on. This would allow economists to offer more nuanced understandings of economic action, from commonplace examples such as “entrepreneurship as mission” or “employment as vocation” to new hybrid forms such as “mixed donations” or “for-profit social ventures and entrepreneurial nonprofits” (Fulton and Blau 2005, 15 and 28).

The point is not to diminish the importance of markets and impersonal, selfinterested exchange but to de-center and de-essentialize them, to open the door to a richer understanding of decentralized social cooperation. As Boulding wisely reminds us, “The greatest threat to the exchange system is the claim that it can do everything. This leads to the equally absurd claim that it can do nothing” (1968, 45). A benefactory economics would help strengthen public understanding and appreciation of markets by emphasizing their “benevolent and developmental qualities” (44) and by relieving some of the economic and political pressures that otherwise tend to be directed at the market system. 20

After Smith, We Still Need Boulding

This paper has attempted to shed light on the longstanding problem of how to define and incorporate philanthropy within modern economic theory. As Boulding would be the first to point out, Adam Smith’s ideas provide a valuable starting point for this endeavor. Smith envisions the human individual as a socialized being animated by multiple and conflicting motivations (including self-love, benevolence, and justice), and the human economy as a space of voluntary action and interaction wherein individuals seek to secure “the cooperation and assistance of great multitudes,” which they require for a flourishing life. Smith then joins these two notions by emphasizing the unplanned economic and social order that arises from our human capacity to interact cooperatively with one another by “treating strangers as though they were honorary relatives or friends” (Seabright 2004).

Boulding’s work also underscores the limits of Smith’s thinking in this area. Smith did not theorize philanthropy as an important means of promoting human welfare in modern society. This remained for him an unfinished project. Hence it is necessary to go beyond Smith in order to re-envision the economy in a satisfactory Tocquevillian, Aristotelian, and Bouldingian fashion as the sphere of private actions—commercial and philanthropic—that directly and indirectly promote human betterment. Our post-Cold War opportunity and challenge is to take up where Boulding left off, to make room for philanthropy within the oikos nomos of twenty-first century civil society, and thereby to reassert the human face of economics as a science of benefaction. Such an endeavor, if successfully executed, would lend credence to Boulding’s optimistic view of economics as “one of the inputs that help to make us human” (1970, 138).

NOTES

- The philanthropic sector is alternately labeled the nonprofit, independent, or mutual aid sector.

- Human betterment is the central normative concept in Boulding’s economic and social theories (Boulding 1985). He defines it in broad, Aristotelian terms as an increase in the goodness or “quality” of human life, and he identifies a series of first-order virtues that generally enhance the quality of life. Among these, he places special emphasis on “the four great virtues of riches, justice, freedom, and peace” (151).

Normative notions of human welfare raise a host of conceptual, ethical, and practical difficulties, such as whether and how it is even possible (or desirable) to specify general criteria for human betterment across time and cultures. Of these difficulties, Boulding writes as follows: The fact that it is not always easy to say unequivocally whether human betterment has taken place between two dates in a given area does not mean that we should give up pursuing human betterment. . . . Things do not have to be clear in order to be real. It is important to know something even where we cannot know everything. . . . This alone is ample justification for pursuing the problem of human betterment and for increasing our skills at it (1985, 29).

The recent work of Sen (1999) and Nussbaum (2003, 2006) addresses some of these difficulties in a manner congenial to Boulding’s approach. - For a sampling of this literature, see previous volumes of Conversations and the pioneering work of Cornuelle ( [1965] 1993, 1983, 1991), the survey essays by Ealy (2002, 2004, 2005), and the articles by Chamlee-Wright, Jones, Tooley and Dixon, and Zimmerman in the June 2005 issue of Economic Affairs.

- This diverse body of work includes experimental economists (V. Smith 1998), development economists (Sen 1999), feminist economists (Folbre 2001, Nelson 2006), post-Marxist economists (Elster 1990, Gintis et al. 2005), and libertarian economists (McCloskey 2006a and 2006b, Storr forthcoming), as well as a new generation of Adam Smith scholars who emphasize the unity of Smith’s moral and economic theories (Sen 1987, Young 1997, Harpham 2000, Rothschild 2001, Jensen 2001, Otteson 2002, Fleischacker 2004, Evensky 2005).

- Amadae describes the Stiglerian view as a Cold War reading of Smith: a reductive translation of “Smith’s analysis of human nature and political economy into the language of self-interested action” by leading U.S. economists in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s (2003, 218).

- According to Stigler, “Smith had one overwhelmingly important triumph: he put into the center of economics the systematic analysis of behavior of individuals pursuing their self-interest under conditions of competition. This theory is the crown jewel of the Wealth of Nations, and it became, and remains to this day, the foundation of the theory of the allocation of resources” (1976, 1200-1201). Smith’s economics, in Stigler’s view, is “a stupendous palace erected upon the granite of self-interest” (1975, 237).

- The distinction between Smithian self-love and Stiglerian self-interest is well documented by Coase (1976), Amadae (2003), and Fleischacker (2004, 66).

- Boulding employs this argument to criticize the concept of Pareto efficiency, which assumes “pure self-interestedness” and no interdependencies (such as malevolence or benevolence) among individual preference functions.

“Anything less descriptive of the human condition could hardly be imagined,” he writes (1970, 126). He describes this hypothetical person in the following passage:

No one in his senses would want his daughter to marry an economic man, who counted every cost and asked for every reward, was never afflicted with mad generosity or uncalculating love, and who never acted out of a sense of inner identity and indeed who had no inner identity even if he was occasionally affected by carefully calculated considerations of benevolence or malevolence (1970, 134-135). - Boulding uses the terms philanthropy, benevolence, and benefaction as interchangeable synonyms.

- The proposed definitional link between “doing good” and “promoting human betterment” is consistent with Boulding’s definition of human betterment as an increase in the quality of human life (1985)

- To be clear, Boulding’s “economic science” definition of economy is not just a conventional definition. It includes large parts of the grants economy and thus “greatly expands the common image of economics” (1981, vi). At the same time, by excluding “non-exchangeables” it conforms to a standard view of economics as “primarily the study of how society is organized through exchange” (1970, 139; emphasis added).

- Boulding defends economics against common criticisms or misunderstandings such as the claim that “cost-benefit analyses in general, or economic principles in general, imply a selfish motivation and an insensitivity to larger issues of malevolence, benevolence, a sense of community, and so on” (1970, 130).

- According to Fleischacker, Smith conceptualizes exchange as an encounter between individual traders and the “impartial spectator” personified by the market itself, with money prices representing the collective “voice” of the innumerable others with whom one is cooperatively linked via the market. This coincides with Fleischacker’s general reading of The Wealth of Nations as a moral (as well as economic) theory of commercial society, based on a broad Smithian definition of moral action as “action of which an impartial spectator would approve” (2004).

- The Chicago Smith/Kirkaldy Smith distinction was coined by Evensky (2005).

- See Fleischacker (2004, 275).

- Young describes economics as a moral science whose central focus ought to be the “common good” of an economic community, the role of economic policy in promoting this common good, and “the responsibilities of the individual members of the community in securing their common good” (1997, 27). Folbre calls for a “move beyond the old capitalism versus communism debate” and “more creative ways of balancing freedom and obligation, achievement and care,” recognizing that “some kinds of care cannot be bought and sold” (2001, xx). Yet neither Young nor Folbre mentions philanthropy (apart from Folbre’s analysis of caregiving within households).

- 17 Like Tocqueville, Cornuelle sees laissez-faire capitalism as potentially corrosive of voluntary public action, yet remains wary of centralized, topdown approaches to these problems (Boesche 1987).

- To this end, Boulding’s “grants economy” includes taxes and government

- This expanded vision of the economic realm resonates with several other recent contributions to this journal. Lloyd, for instance, echoes Tocqueville in raising incisive questions about the nexus of philanthropy, politics, and economics—including a wariness of accepting the absolute authority of markets. Lloyd argues for “a Tocquevillian, modern public action solution for the problems of modernity, one that retains spontaneous human initiative and yet appeals to the civic dimension of human existence” (2004, 105; original emphasis). Turner articulates a distinct role for philanthropy as part of the gift economy

- Bowles et al. (2005, 4) suggest that one important role for a benefactory economics would be to “support socially valued outcomes, not only by harnessing selfish motives to socially valued ends but also by evoking, cultivating, and empowering public-spirited motives.”

REFERENCES

Amadae, S. M. 2003. Rationalizing Capitalist Democracy: The Cold War Origins of Rational Choice Liberalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boesche, Roger. 1987. The Strange Liberalism of Alexis de Tocqueville. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Boettke, Peter J. 2000. “Why Read the Classics in Economics?” Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Features/feature2.html, February.

Boettke, Peter J. and David L. Prychitko. 2004. “Is an Independent Nonprofit Sector Prone to Failure? Toward an Austrian Interpretation of Nonprofit and Voluntary Action.” Conversations on Philanthropy I: 1-40.

Boulding, Kenneth E. 1962. “Notes on a Theory of Philanthropy.” In Frank G. Dickenson (ed.),Philanthropy and Public Policy, 57-71. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Reprinted in Fred R. Glahe (ed.), Collected Papers of Kenneth Boulding, Volume II, 235-249. Boulder: Colorado: Associated University Press, 1971. Page numbers refer to 1971 reprint.

——— 1965. “The Difficult Art of Doing Good.” Colorado Quarterly, 13 (Winter): 197-211. Reprinted in Larry D. Singell (ed.), Collected Papers of Kenneth Boulding, Volume IV, 247-261. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1974. Page numbers refer to 1974 reprint.

——— 1968. Beyond Economics: Essays on Society, Religion, and Ethics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

——— 1970. Economics as a Science. New York: McGraw-Hill.

——— 1971. “After Samuelson, Who Needs Adam Smith?” History of Political Economy, 3(2): 225-237.

——— 1973. The Economy of Love and Fear: A Preface to Grants Economics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

——— 1976. Adam Smith as an Institutional Economist. Memphis, TN: P.K. Seidman Foundation.

——— 1981. A Preface to Grants Economics: The Economy of Love and Fear. New York: Praeger.

——— 1985. Human Betterment. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Chamlee-Wright, Emily. 2004. “Comment on Boettke and Prychitko.” Conversations on Philanthropy I: 45-51.

——— 2005. “Fostering Sustainable Complexity in the Microfinance Industry: Which Way Forward?” Economic Affairs, 25 (2): 5-12.

Coase, Ronald H. 1976. “Adam Smith’s View of Man.” Journal of Law and Economics, 19 (3): 529-546.

Cornuelle, Richard C. [1965], 1993. Reclaiming the American Dream: The Role of Private Individuals and Voluntary Associations. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

——— 1983. Healing America. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

——— 1991. “New Work for Invisible Hands: A Future for Libertarian Thought.” The Times Literary Supplement, April 5.

Dawes, Robyn M. and Richard T. Thaler. 1988. “Cooperation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2 (3): 187-197.

Ealy, Lenore T. 2002. “Richard Cornuelle Bibliographic Essay.” Unpublished manuscript. Indianapolis: Donors Trust.

——— 2004. “Introduction.” Conversations on Philanthropy I: i-iii.

——— 2005. “The Philanthropic Enterprise: Reassessing the Means and Ends of Philanthropy.”Economic Affairs, 25 (2): 2-4.

Elster, Jon. 1990. “Selfishness and Altruism.” In Jane J. Mansbridge (ed.), Beyond Self-Interest, 44-52. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Evensky, Jerry. 2005. Adam Smith’s Moral Philosophy: A Historical and Contemporary Perspective on Markets, Law, Ethics, and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fleischacker, Samuel. 2004. On Adam Smith’s ‘Wealth of Nations’: A Philosophical Companion. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Folbre, Nancy. 2001. The Invisible Heart: Economics and Family Values. New York: The New York Press.

Fulton, Katherine and Andrew Blau. 2005. Looking Out for the Future: An Orientation for Twenty-First Century Philanthropists. Cambridge, MA: The Monitor Group.

Gintis, Herbert, Samuel Bowles, Robert T. Boyd, and Ernst Fehr. 2005. Moral Sentiments and Material Interests: The Foundations of Cooperation in Economic Life. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harpham, Edward J. 2000. “The Problem of Liberty in the Thought of Adam Smith.” Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 22 (2): 217-237.

Jensen, Hans E. 2001. “Amatya Sen as a Smithesquely Worldly Philosopher: Or, Who Needs Sen When We Have Smith?” Unpublished paper. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee, Department of Economics.

Jones, Paul A. 2005. “Philanthropy and Enterprise in the British Credit Union Movement.”Economic Affairs, 25 (2): 13-19.

Lloyd, Gordon. 2004. “Comment on Ealy.” Conversations on Philanthropy I: 101-105.

McCloskey, Deirdre N. 2006a. The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

——— 2006b. “The Hobbes Problem: From Machiavelli to Buchanan.” Unpublished paper presented as the James M. Buchanan lecture at George Mason University, April 7.

Mirowski, Philip. 2001. “Refusing the Gift.” In Stephen Cullenberg, Jack Amariglio, and David Ruccio (eds.), Postmodernism, Economics, and Knowledge, 431-458. London: Routledge.

Nelson, Julie A. 2006. Economics for Humans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2003. “Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice.” Feminist Economics 9 (2-3): 33-59.

——— 2006. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, and Species Membership. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Otteson, James R. 2002. Adam Smith’s Marketplace of Life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

——— Forthcoming. “Markets, Markets Everywhere: A Brief Response to Critics.” Adam Smith Review, volume 2.

Rothschild, Emma. 2001. Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet, and the Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Salamon, Lester M. 1995. Partners in Public Service: Government-Nonprofit Relations in the Modern Welfare State. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Seabright, Paul. 2004. The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1987. On Ethics and Economics. Oxford: Blackwell. ——— 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

Smith, Adam. [1759] 1976a The Theory of Moral Sentiments. David D. Raphael and Alec L. Macfie (eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——— [1776] 1976b An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Roy H. Campbell and Andrew S. Skinner (eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Vernon L. 1998. “The Two Faces of Adam Smith.” Southern Economic Journal, 65 (1): 1-19.

Stigler, George J. 1975. “Smith’s Travels on the Ship of State.” In Andrew Skinner and Thomas Wilson (eds.), Essays on Adam Smith, 237-246. Oxford: Clarendon.

——— 1976. “The Successes and Failures of Professor Smith.” Journal of Political Economy, 84 (December): 1199-1213.

Storr, Virgil H. Forthcoming. “The Market as a Social Space: Austrian Economics, Economic Sociology, and the Social Significance of Economic Relationships.” Review of Austrian Economics.

Tooley, James and Pauline Dixon. 2005. “Is There a Conflict Between Commercial Gain and Concern for the Poor? Evidence from Private Schools for the Poor in India and Nigeria.” Economic Affairs, 25 (2): 20-26.

Turner, Frederick. 2005. “Creating a Culture of Gift.” Conversations on Philanthropy II: 27-58.

Wight, Jonathan B. and Douglas E. Hicks. 2005. “Disaster Relief: What Would Adam Smith Do?”Christian Science Monitor, January 18, p. 9.

Young, Jeffrey T. 1997. Economics as a Moral Science: The Political Economy of Adam Smith. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar.

Zimmerman, Drake. 2005. “Rotarians Against Malaria: Philanthropic Enterprise in Action.”Economic Affairs, 25 (2): 34-36.